As I wrote in my previous blogpost, AI feels to me like a Swiss army knife: capable of many things, but not always clear on which tool is right for which job. This is particularly hard for someone like me; someone who prefers understanding how things work before starting to experiment with them (unlike most of my engineer friends).

Luckily, during our internal Innovation Days, we had a full GitHub Copilot day in collaboration with Microsoft that helped me understand things a bit better. Here are my key takeaways.

This is my personal understanding and not an authoritative article. And even though it is written by a human, that doesn’t mean that it is hallucination-free.

1. AI agents vs AI assistants

A simple way I’ve found to distinguish between an agent and an assistant is to ask: “Does it wait for me to do the job, or does it do it on its own?” If it waits, it’s an assistant; if not, it’s likely an agent. For example, using “vanilla” GitHub Copilot gives you an AI coding assistant, while GitHub Copilot Agents can perform coding tasks for you autonomously. Choosing between an assistant and an agent is one of the first decisions about how much you want to trust your work to AI.

Assistants and agents often work together even if we are not conscious of it. Under the hood, an AI assistant might use AI agents to produce results that are then shown to you for approval. For instance, GitHub Copilot (the assistant) may call an internal agent, which then finds the best resources to write the code you requested. The agent doesn’t ask for your permission regarding which resources to use to write the code, but the assistant waits for your approval before submitting the generated code.

2. AI agents and assistants serve a purpose

Both of these AI entities exist to serve a purpose. In the case of GitHub Copilot, you have a coding assistant which has one purpose: to code. Being mindful of the purpose of AI tools, helps us assign them tasks they are actually programmed to do. That can save us frustration when their answers fall outside their intended domain or purpose.

You can combine multiple AI “creatures” with different purposes to produce better results. For example, you can have a Product Manager assistant which purpose is to break down a user need into small releasable increments or a Technical assistant that proposes a structure for the documentation of a new feature. Just like with humans, the results that will be produced by their interaction depend greatly on their underlying knowledge. And this is where intelligence comes into play…

3. Agents and assistants need Intelligence

Professor Russel Ackoff defines intelligence as “the ability to increase efficiency.” Agents and assistants need intelligence, i.e., data turned into information, then information turned into knowledge to do their job and help us be more efficient. This intelligence can come from the user coordinating the agents or from external resources.

3.1 User-provided intelligence

In GitHub Copilot, this can be a repository instructions file or stored prompts. The content of these two files can be used as guardrails for the assistant’s output. In my opinion, instruction files need to be written or driven by the most experienced engineer in a team. These are the people that know the tips and tricks of good coding practices. It might be a challenge though, to convert their knowledge as prose in a markdown file. For junior developers, the exercise is to learn to capture and document their day-to-day learning, which could then be added to the instruction and prompt files.

3.2 External intelligence

While a team may know their local context, agents and assistants with access to more intelligence can produce more context-aware results. For example, if an agent can query a document with your product requirements before suggesting code, the results will likely be better. This “external intelligence” is often referred to as “Tools.” When using tools like GitHub Copilot, knowing what external tools are at your disposal is the first step in understanding how much context it has for its outputs.

Bonus: By providing intelligence and guardrails upfront to coding assistants, continuous delivery pipelines theoretically should get much “lighter” as quality will be baked into the code. Will we eventually audit code creation as thoroughly as we audit pipelines?

4. Tool results are deterministic their usage after a prompt is not

This one took me a while to grasp. Take Jira as an example: it’s a tool with information and functionality that agents or assistants can use. Within Jira, you can define smaller tools (like reading or writing to a project), each returning a deterministic result (e.g., creating a new issue). These tools within tools have names and descriptions that the agent or assistant’s LLM uses to decide whether to call them after a prompt. If the description is vague (“does something in Jira”), it’s less likely to be used. Product managers and documentation writers should pay close attention to these descriptions, if they want their tools to be successfully used by AI assistants or agents. “Developer English” might just not be enough.

5. Agents and assistants need a way to access intelligence

There are various ways for agents and assistants to access the available intelligence. One way is to call, for example, the Jira API in a GitHub Actions workflow and let GitHub Copilot use the results. This is an indirect way of using tools like Jira, and it is an experience close to what we get with pipelines: do something (write code), get feedback (read the Jira issue), and then act on it (incorporate the feedback to get a new result).

Another way to give access is through MCP (Model Context Protocol). In this case, the tool is “packaged” in an MCP server and can be used directly by Copilot, allowing it to consider the tool’s output before making suggestions.

6. Using AI productively isn’t cheap

To leverage AI capabilities, you must pay a price. Sometimes it’s obvious (license fees); other times, it’s less visible (making everything enterprise-ready).

6.1 Paying with money for access

Licensing is the most visible price tag. Your company needs to buy licenses for AI agents, assistants, and the different LLM that support them. There is also a cost associated with the tokens used, though I assume this is included in the license agreement. While I am personally not interested to dive into pricing details, I do believe that being aware of costs can make us all more mindful about usage of these tools.

6.2 Paying with time to make them enterprise ready

Without wanting to sound dramatic, in an enterprise setting, improper use of AI tools can be catastrophic. For example, Copilot might submit code from an open-source library with a license that could make your enterprise code available for public use. Strong legal, technical, ethical, and privacy guardrails need to be in place to govern the access and usage of AI tools. Streamlining the process of setting these guardrails and the process itself can be frustrating for those eager to use new technology for their work.

6.3 Paying with time to learn new skills

Watching the Microsoft evangelists “fine-tune” Copilot reminded me of learning to work in Continuous Delivery in 2012. Even though it felt that I was working faster, that wasn’t really the case. It was just that my work time was distributed differently. It was now evenly spread over a period of time, making development more efficient.

Just announcing that you’re practicing Continuous Delivery without changing anything doesn’t make you more efficient. Likewise, simply getting a GitHub Copilot license doesn’t automatically make you more efficient either. I assume most developers can figure out the tool’s functionality pretty fast. But setting good guardrails and fine-tuning the process to get the real benefits takes much more time. I am afraid that development teams are not given the necessary time to experiment and learn this new way of working. Additional support through centralised instructions, sharing prompt tips and communities of practice could also support the transition.

Bonus point: There is also an environmental cost of using AI capabilities, but I can’t say that I deeply understand the impact.

7. There is lots of inception involved

Honestly, it’s all a bit mind-boggling. To use AI assistants and agents effectively, you need to guide them with instructions and prompts which are sometimes created by other agents and assistants. You can even use tools written by AI to generate code that create more assistants and agents. This recursive aspect is a little scary. If we all depend on these tools and stop generating original ideas, won’t we all end up doing the same thing?

Final thoughts

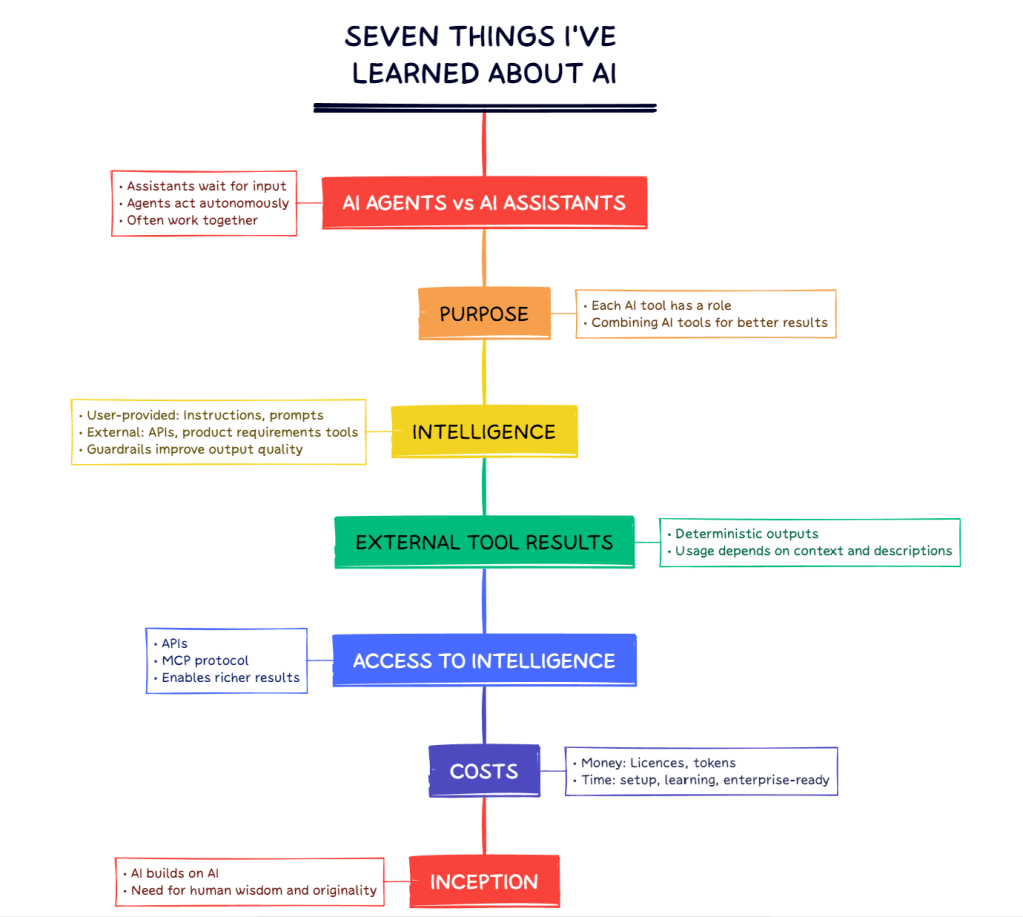

I always find it useful to visualise what I read and write, so that I can remember it easier later.

Overall, I believe AI tooling has great potential to make us more productive and efficient. After last week’s event, I also know that this doesn’t happen out-of-the-box, but requires a conscious effort to learn and adapt to working in a new way.

Nevertheless, a word of caution from professor Ackoff::

From all this I infer that although we are able to develop computerized information-,

knowledge-, and understanding-generating systems, we will never be able to generate wisdom by such systems. It may well be that wisdom—which is essential for the pursuit of ideals or ultimately valued ends—is the characteristic that differentiates man from machines. For this reason, if no other, the educational process should allocate as much time to the development and exercise of wisdom as it does to the development and exercise of intelligence.

As long as we keep investing in “the development and exercise of wisdom,” I believe we’ll do just fine.